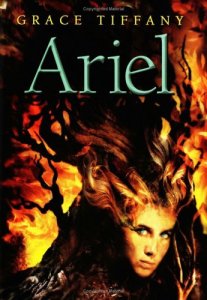

Ariel by Grace Tiffany. Fiction. Copyright 2005. ISBN 9780060753276

Story:

In Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Ariel is a magical spirit that lives on Prospero’s island, serving the magician and desiring only freedom. In Grace Tiffany’s Ariel, Ariel is a conniving liar who cares only for tricks and conquest, a manipulator of everyone and everything she comes across. What this means for the unfortunate souls who wash up on the shores of her island is uncertain at best.

Style and Plot:

To say Ariel is an adaptation of The Tempest isn’t quite accurate. Author Grace Tiffany uses the same characters and setting as the famous play, but many things are changed—Ariel is now female, motivations are switched around, origins are developed or expounded on— making the final product something very different from Shakespeare’s work.

Tiffany adds much to The Tempest, developing the geographical context and giving the events a timeline (Ariel was created in the 58th year), which gives the story some striking implications as it progresses. She also gives several characters more dimension, fleshing out their personalities and making what they do much more understandable and accessible than Shakespeare’s original text might allow.

However, the book reads as though the events are being described by a distant observer—apart from the occasional instance where the reader might be drawn in by a powerful emotion, it all feels a bit detached and is mildly interesting at best. Tiffany mixes historical events with Shakespeare’s fiction, which adds relevance to the plot, but it often comes off as clunky. Most of all, while the writing is technically good, it lacks energy. It’s hard to be pulled into the story when it feels like it’s just being passively told, with no real investment.

Characterization:

The titular character is the embodiment of flight and fancy, having been born of the imagination of a dying sailor. She doesn’t understand anything on a human level, is selfish, conniving, and power-hungry (what need has a spirit for conquest?). Nothing that she does can be expected to follow any semblance of logic, rationale, or sympathy. While this effectively gives her a two-dimensional personality, with no care for anything but herself, she’s still a curious character. As humans with a natural sense of empathy, we still find something intriguing about a person that just doesn’t care. Tiffany did a good job of pulling Ariel’s mindset off and letting it affect every little thing she does over the course of the novel.

Tiffany took as many liberties with the rest of the characters as she did with the storyline itself. Though we run into every named character that appears in The Tempest, most of them are changed, some to drastic proportions. Sycorax is Nordic, Prospero isn’t nearly as mystical, Miranda and Caliban have their own thing going on, and the party from Milan is not all it seems to be.

Because of these changes in who the characters fundamentally are, the results of the story are not what the reader might expect. If the ending is held to the standard of Shakespeare (a reasonable standard, considering that Ariel was written by a scholar of Shakespeare), it is far too neat and unsatisfying— but if the book is judged on its own merit, with the understanding that it should be seen as a work separate from The Tempest, then the ending can be read in a better light. It’s hardly dazzling either way, but most Shakespeare enthusiasts will be, at the least, interested in hearing Tiffany’s ideas.

Ariel expounds on the characters and setting of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, but needs more vitality to make it worth remembering. 3 out of 5 stars.